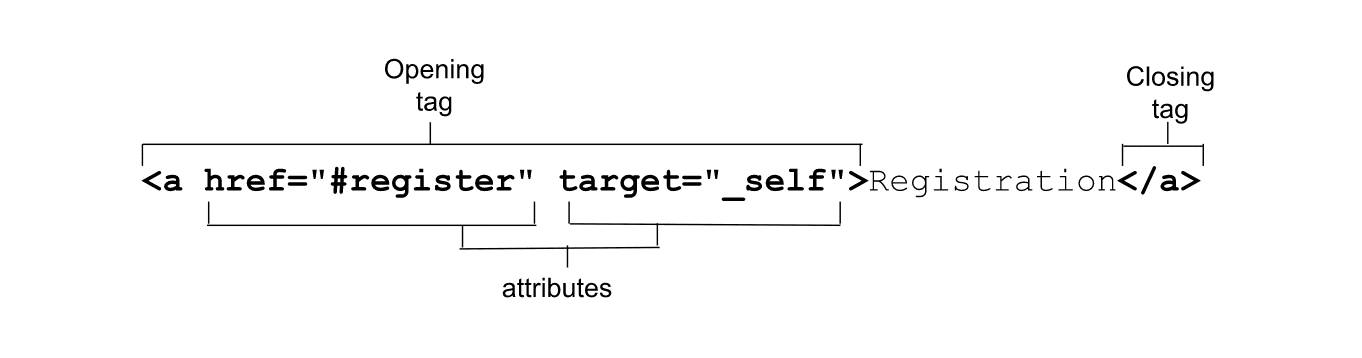

Attributes were briefly discussed in Overview of HTML. It's time for a deep dive.

Attributes are what make HTML so powerful. Attributes are space-separated names and name/value pairs appearing in the opening tag, providing information about and functionality for the element.

Attributes define the behavior, linkages, and functionality of elements. Some attributes are global, meaning they can appear within any element's opening tag. Other attributes apply to several elements but not all, while other attributes are element-specific, relevant only to a single element. In HTML, all attributes except boolean, and to some extent enumerated attributes, require a value.

If an attribute value includes a space or special characters, the value must be quoted. For this reason and improved legibility, quotations are always recommended.

While HTML isn't case-sensitive, some attribute values are. Values that are part of the HTML specification are case-insensitive. Strings values that are defined, such as class and ID names, are case-sensitive. If an attribute value is case-sensitive in HTML, it's case-sensitive when used as an attribute selector in CSS and in JavaScript; otherwise, it's not.

<!-- the type attribute is case insensitive: these are equivalent -->

<input type="text">

<input type="TeXt">

<!-- the ID attribute is case sensitive: they are not equivalent -->

<div id="myId">

<div id="MyID">

Boolean attributes

If a boolean attribute is present, it is always true. Boolean attributes include autofocus, inert, checked, disabled,

required, reversed, allowfullscreen, default, loop, autoplay, controls, muted, readonly, multiple, and selected.

If one (or more) of these attributes is present, the element is disabled, required, readonly, etc. If not present, it isn't.

Boolean values can either be omitted, set to an empty string, or be the name of the attribute; but the value doesn't have to actually

be set to the string true. All values, including true, false, and 😀, while invalid, will resolve to true.

These three tags are equivalent:

<input required>

<input required="">

<input required="required">

If the attribute value is false, omit the attribute. If the attribute is true, include the attribute but don't provide a value.

For example, required="required" is not a valid value in HTML; but as required is boolean, invalid values resolve to true.

But as invalid enumerated attributes don't necessarily resolve to the same value as missing values, it is easier to get into the

habit of omitting values than it is to remember which attributes are boolean versus enumerated and potentially provide an invalid value.

When toggling between true and false, add and remove the attribute altogether with JavaScript rather than toggling the value.

const myMedia = document.getElementById("mediaFile");

myMedia.removeAttribute("muted");

myMedia.setAttribute("muted");

Enumerated attributes

Enumerated attributes are sometimes confused with boolean attributes. They are

HTML attributes that have a limited set of predefined valid values.

Like boolean attributes, they have a default value if the attribute is present

but the value is missing. For example, if you include <style contenteditable>,

it defaults to <style contenteditable="true">.

Unlike boolean attributes, though, omitting the attribute doesn't mean it's

false. A present attribute with a missing value isn't necessarily true, and the

default for invalid values isn't necessarily the same as a null string.

Continuing the example, contenteditable defaults to inherit if missing or

invalid, and can be explicitly set to false.

The default value depends on the attribute. Unlike boolean values, attributes

aren't automatically "true" if present. If you

include <style contenteditable="false">, the element is not editable. If the value is invalid, such as <style contenteditable="😀">,

or, surprisingly, <style contenteditable="contenteditable">, the value is invalid and defaults to inherit.

In most cases with enumerated attributes, missing and invalid values are the same. For example, if the type attribute on an <input>

is missing, present but without a value, or has an invalid value, it defaults to text. While this behavior is common, it is not a rule.

Because of this, it's important to know which attributes are boolean versus enumerated; omit values if possible so you don't get them wrong, and look up the value as needed.

Global attributes

Global attributes are attributes that can be set on any HTML element, including elements in the <head>. There are more than

30 global attributes. While these can all, in theory, be added to any HTML element, some global attributes have no effect

when set on some elements; for example, setting hidden on a <meta> as meta content is not displayed.

id

The global attribute id is used to define a unique identifier for an element. It serves many purposes, including:

- The target of a link's fragment identifier.

- Identifying an element for scripting.

- Associating a form element with its label.

- Providing a label or description for assistive technologies.

- Targeting styles with (high specificity or as attribute selectors) in CSS.

The id value is a string with no spaces. If it contains a space, the document won't break, but you'll have to target the

id with escape characters in your HTML, CSS, and JS. All other characters are valid. An id value can be 😀 or .class,

but is not a good idea. To make programming easier for your current and future self, make the id's first character a letter,

and use only ASCII letters, digits, _, and -. It's good practice to come up with an id naming convention and then stick to it,

as id values are case-sensitive.

Theid should be unique to the document. The layout of your page probably won't break if an id is used more than once,

but your JavaScript, links, and element interactions may not act as expected.

Link fragment identifier

The navigation bar includes four links. We will cover the link element later, but for now, realize links aren't restricted to HTTP-based URLs. They can be fragment identifiers to sections of the page in the current document (or in other documents).

On the machine learning workshop site, the navigation bar in the page header includes four links:

The href attribute provides the hyperlink that activating the link directs the user to. When a URL includes a hash mark (#)

followed by a string of characters, that string is a fragment identifier. If that string matches an id of an element in the

web page, the fragment is an anchor, or bookmark, to that element. The browser will scroll to the point where the anchor is defined.

These four links point to four sections of our page identified by their id attribute. When the user clicks on any of the

four links in the navigation bar, the element linked to by the fragment identifier, the element containing the matching ID

minus the #, scrolls into view.

The <main> content of the machine learning workshop has four sections with ids. When the site visitor clicks on one of the

links in the <nav>, the section with that fragment identifier scrolls into view. The markup is similar to:

<section id="reg">

<h2>Machine Learning Workshop Tickets</h2>

</section>

<section id="about">

<h2>What you'll learn</h2>

</section>

<section id="teachers">

<h2>Your Instructors</h2>

<h3>Hal 9000 <span>&</span> EVE</h3>

</section>

<section id="feedback">

<h2>What it's like to learn good and do other stuff good too</h2>

</section>

Comparing the fragment identifiers in the <nav> links, you'll notice that each

matches the id of a <section> in <main>.

The browser gives us a free "top of page" link. Setting href="#top",

case-insensitive, or href="#", will scroll the user to the top of the page.

The hash-mark separator in the href isn't part of the fragment identifier. The

fragment identifier is always the last part of the URL and is not sent to

the server.

CSS selectors

In CSS, you can target each section using anselector, such as #feedback.

For less specificity,

use a case-sensitive

attribute selector, [id="feedback"].

Scripting

On MLW.com, there is an easter egg for mouse users only. Clicking the light

switch toggles the page on and off.

The markup for the light switch image is:

<img src="svg/switch2.svg" id="switch"

alt="light switch" class="light" />

The id attribute can be used as the parameter for the getElementById() method and, with a # prefix, as part of a

parameter for the querySelector() and querySelectorAll() methods.

const switchViaID = document.getElementById("switch");

const switchViaSelector = document.querySelector("#switch");

Our one JavaScript function makes use of this ability to target elements by

their id attribute:

<script>

/* Switch is a reserved word in JavaScript, so instead, we use onoff */

const onoff = document.getElementById('switch');

onoff.addEventListener('click', function(){

document.body.classList.toggle('black');

});

</script>

<label>

The HTML <label> element has a for attribute that takes as its value the id of the form control with which it is associated.

Creating an explicit label by including an id on every form control and pairing each with the label's for attribute ensures

that every form control has an associated label.

While each label can be associated with exactly one form control, a form control may have more than one associated label.

If the form control is nested between the <label> opening and closing tags, the for and id attributes

aren't required: this is called an "implicit" label. Labels let all users know what each form control is for.

<label>

Send me a reminder <input type="number" name="min"> before the workshop resumes

</label>.

The association between for and id makes the information available to users of assistive technologies. In addition,

clicking anywhere on a label gives focus to the associated element, extending the control's click area. This isn't just helpful

to people with dexterity issues making mousing less accurate; it also helps every mobile device user with fingers wider than a radio

button.

In this code example, the fake fifth question of a fake quiz is a single select multiple-choice question. Each form control has an explicit

label, with a unique id for each. To ensure we don't accidentally duplicate an ID, the ID value is a combination of the question number and the value.

When including radio buttons, as the labels describe the value of the radio buttons, we encompass all the same-named buttons in a <fieldset>

with the <legend> being the label, or question, for the entire set.

Other accessibility uses

The use of id in accessibility and usability goes beyond labels. In

introduction to text, a <section>

was converted into region landmark by referencing the id of an <h2> as the value of the <section>'s aria-labelledby to provide

the accessible name:

<section id="about" aria-labelledby="about_heading">

<h2 id="about_heading">What you'll learn</h2>

There are over 50 aria-* states and properties that can be used to ensure accessibility. aria-labelledby, aria-describedby,

aria-details, and aria-owns take as their value a space-separated id reference list. aria-activedescendant, which

identifies the focused descendant element, takes as its value a single id reference: that of the single element

that has focus (only one element can be focused at a time).

class

The class attribute provides an additional way of targeting elements with CSS

(and JavaScript), but serves no other purpose in HTML (though frameworks and

component libraries may use them). The class attribute takes as its value a

space-separated list of the case-sensitive classes for the element.

Building a sound semantic structure enables the targeting of elements based on their placement and function. Sound structure enables the use of descendant element selectors, relational selectors, and attribute selectors. As you learn about attributes, consider how elements with the same attributes or attribute values can be styled. It's not that you shouldn't use the class attribute, it's just that most developers don't realize they often don't need to.

Thus far, MLW hasn't used any classes. Can a site be launched without a single class name? We'll see.

style

The style attribute enables applying inline styles, which are styles applied to the single element on which the attribute is set.

The style attribute takes as its value CSS property value pairs, with the value's syntax being the same as the contents of a

CSS style block: properties are followed by a colon, just like in CSS, and semicolons end each declaration, coming after the value.

The styles are only applied to the element on which the attribute is set.

Descendants inherit inherited property values, unless they're overridden by

other style declarations on nested elements or in <style> blocks or

stylesheets. As the value comprises the equivalent of the contents

of a single style block applied to that element only, it can't be used for

generated content, to create keyframe animations, or to apply any

other at-rules.

While style is indeed a global attribute, using it is not recommended. Rather,

define styles in a separate file or files.

That said, the style attribute can come in handy during development to enable quick styling such as for testing purposes. Then take the

'solution' style and stick it in your linked CSS file.

tabindex

The tabindex attribute can be added to any element to enable it to receive focus. The tabindex value defines whether it

gets added to the tab order, and, optionally, into a non-default tabbing order.

The tabindex attribute takes as its value an integer. A negative value

(the convention is to use -1) makes an element capable

of receiving focus, such as with JavaScript, but doesn't add the element to the tabbing sequence. A tabindex value of 0 makes

the element focusable and reachable with tabbing, adding it to the default tab order of the page in source code order. A value of 1

or more puts the element into a prioritized focus sequence and is not recommended.

On this page, there is a share functionality using a <share-action> custom element acting as a <button>. The tabindex of zero

is included to add the custom element into the keyboard default tabbing order:

<share-action authors="@estellevw" data-action="click" data-category="web.dev" data-icon="share" data-label="share, twitter" role="button" tabindex="0">

<svg aria-label="share" role="img" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<use href="#shareIcon" />

</svg>

<span>Share</span>

</share-action>

The role of button informs screen reader users that this element should behave like a button. JavaScript is used to ensure

the button functionality promise is kept; including handling both click and keydown events as well as handling Enter and Space key keypresses.

Form controls, links, buttons, and content editable elements are able to receive focus; when a keyboard user hits the tab key,

focus moves to the next focusable element as if they had tabindex="0" set. Other elements are not focusable by default. Adding the tabindex

attribute to those elements enables them to receive focus when they would otherwise not.

If a document includes elements with a tabindex of 1 or more, they're

included in a separate tab sequence. In the CodePen, tabbing begins in a

separate sequence, in order of lowest value to highest value, before going

through those in the regular sequence in source order.

Altering the tabbing order can create a really bad user experience. It makes it difficult to rely on assistive technology, keyboards and screen readers alike, to navigate your content. It is also difficult as a developer to manage and maintain. Focus is important; there is an entire module discussing focus and focus order.

role

The role attribute is part of the ARIA specification,

rather than the WHATWG HTML specification. The role attribute can

be used to provide semantic meaning to content, enabling screen readers to inform site users of an object's expected user interaction.

There are a few common UI widgets, such as comboboxes,

menubars, tablists,

and treegrids, that have no native HTML equivalent.

For example, when creating a tabbed design pattern, the tab, tablist and

tabpanel roles can be used. Someone who can physically see

the user-interface has learned by experience how to navigate the widget and make different panels visible by clicking on associated tabs.

Including the tab role with <button role="tab"> when a group of buttons is used to show different panels lets the screen reader user know

that the <button> that currently has focus can toggle a related panel into view rather than implementing typical button-like functionality.

The role attribute doesn't change browser behavior or alter keyboard or pointer device interactions—adding role="button"to a <span>

does not turn it into a <button>. This is why using semantic HTML elements for their intended purpose is recommended. However, when using

the right element is not possible, the role attribute enables informing screen reader users when a non-semantic element has been retrofitted

into a semantic element's role.

contenteditable

An element with the contenteditable attribute set to true is editable, is focusable, and is added to the tab order as if

tabindex="0" were set. Contenteditable is an enumerated attribute supporting the values true and false, with a default value of inherit

if the attribute is not present or has an invalid value.

These three opening tags are equivalent:

<style contenteditable>

<style contenteditable="">

<style contenteditable="true">

If you include <style contenteditable="false">, the element is not editable (unless it's by default editable, like a <textarea>).

If the value is invalid, such as <style contenteditable="😀"> or <style contenteditable="contenteditable">, the value defaults to inherit.

To toggle between states, query the value of the HTMLElement.isContentEditable readonly property.

const editor = document.getElementById("myElement");

if(editor.contentEditable) {

editor.setAttribute("contenteditable", "false");

} else {

editor.setAttribute("contenteditable", "");

}

Alternatively, this property can be specified by setting editor.contentEditable to true, false, or inherit.

Global attributes can be applied to all elements, even <style> elements. You can use attributes and a bit of CSS to make a live CSS editor.

<style contenteditable>

style {

color: inherit;

display:block;

border: 1px solid;

font: inherit;

font-family: monospace;

padding:1em;

border-radius: 1em;

white-space: pre;

}

</style>

Try changing the color of the style to something other than inherit. Then try changing the style to a p selector.

Don't remove the display property or the style block will disappear.

Custom attributes

We've only touched the surface of HTML global attributes. There are even more attributes that apply to only one or a limited set of elements. Even with hundreds of defined attributes, you may have a need for an attribute that isn't in the specification. HTML has you covered.

You can create any custom attribute you want by adding the data- prefix. You can name your attribute anything that starts with data-

followed by any lowercase series of characters that don't start with xml and don't contain a colon (:).

While HTML is forgiving and won't break if you create unsupported attributes that don't start with data, or even if you start

your custom attribute with xml or include a :, there are benefits to creating valid custom attributes that begin with data-.

With custom data attributes you know that you aren't accidentally using an existing attribute name. Custom data attributes are future-proof.

While browsers won't implement default behaviors for any specific data- prefixed attribute, there is a built-in dataset API

to iterate through your custom attributes. Custom properties are an excellent way of communicating application-specific information

in JavaScript. Add custom attributes to elements in the form of data-name and access these through the DOM using dataset[name]

on the element in question.

<blockquote data-machine-learning="workshop"

data-first-name="Blendan" data-last-name="Smooth"

data-formerly="Margarita Maker" data-aspiring="Load Balancer"

data-year-graduated="2022">

HAL and EVE could teach a fan to blow hot air.

</blockquote>

You can use getAttribute() using the full attribute name, or you can take advantage of the simpler dataset property.

el.dataset["machineLearning"]; // workshop

e.dataset.machineLearning; // workshop

The dataset property returns a DOMStringMap object of each element's data- attributes. There are several custom attributes

on the <blockquote>. The dataset property means you don't need to know what those custom attributes are in order to access their

names and values:

for (let key in el.dataset) {

customObject[key] = el.dataset[key];

}

The attributes in this article are global, meaning they can be applied to any HTML element (though they don't all have an impact on

those elements). Up next, we take a look at the two attributes from the intro image that we didn't address—target and href—and

several other element-specific attributes as we take a deeper look into links.

Check your understanding

Test your knowledge of attributes.

An id should be unique in the document.

Select the correctly formed custom attribute.

data-birthdaybirthdaydata:birthday