With over 100 HTML elements and the ability to create custom elements, there are infinite ways to mark up your content. But, some ways—notably semantically—are better than others.

Semantic means "relating to meaning". Writing semantic HTML means using HTML elements to structure your content based on each element's meaning, not its appearance.

This series hasn't covered many HTML elements yet, but even without knowing HTML, the following two code snippets show how semantic markup can give content context. Both use a word count instead of ipsum lorem to save some scrolling—use your imagination to expand "thirty words" into 30 words:

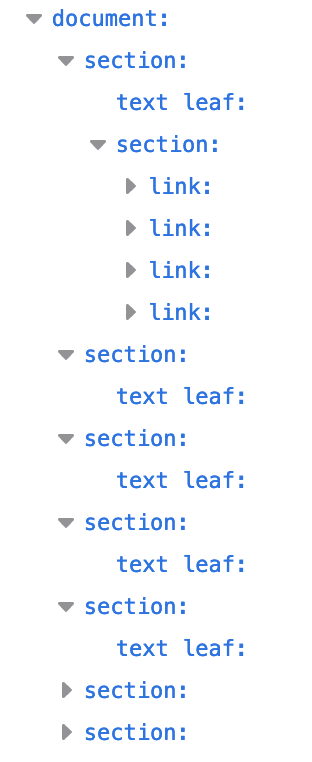

The first code snippet uses <div> and <span>, two elements with no semantic value.

<div>

<span>Three words</span>

<div>

<a>one word</a>

<a>one word</a>

<a>one word</a>

<a>one word</a>

</div>

</div>

<div>

<div>

<div>five words</div>

</div>

<div>

<div>three words</div>

<div>forty-six words</div>

<div>forty-four words</div>

</div>

<div>

<div>seven words</div>

<div>sixty-eight words</div>

<div>forty-four words</div>

</div>

</div>

<div>

<span>five words</span>

</div>

Do you get a sense of what those words expand to? Not really.

Let's rewrite this code with semantic elements:

<header>

<h1>Three words</h1>

<nav>

<a>one word</a>

<a>one word</a>

<a>one word</a>

<a>one word</a>

</nav>

</header>

<main>

<header>

<h2>five words</h2>

</header>

<section>

<h2>three words</h2>

<p>forty-six words</p>

<p>forty-four words</p>

</section>

<section>

<h3>seven words</h3>

<p>sixty-eight words</p>

<p>forty-four words</p>

</section>

</main>

<footer>

<p>five words</p>

</footer>

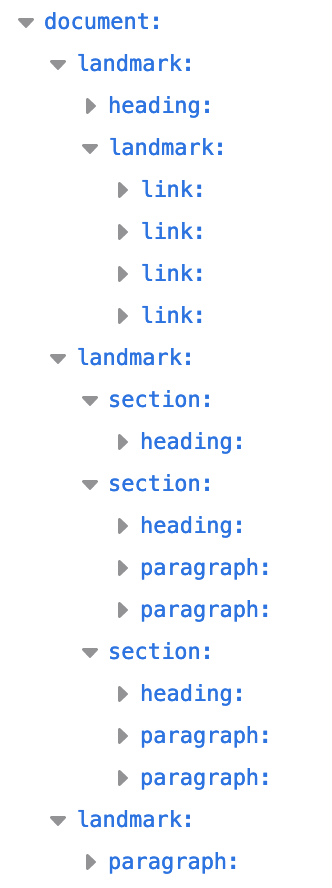

Which code block conveyed meaning? Using only the non-semantic elements of <div> and <span>, you really can't tell what the content in the first code block represents. The second code example, with semantic elements, provides enough context for a non-coder to decipher the purpose and meaning without having ever encountered an HTML tag. It definitely provides enough context for the developer to understand the outline of the page, even if they don't understand the content, such as content in a foreign language.

In the second code block, we can understand the architecture even without understanding the content because semantic elements provide meaning and structure. You can tell that the first header is the site's banner, with the <h1> likely to be the site name. The footer is the site footer: the five words may be a copyright statement or business address.

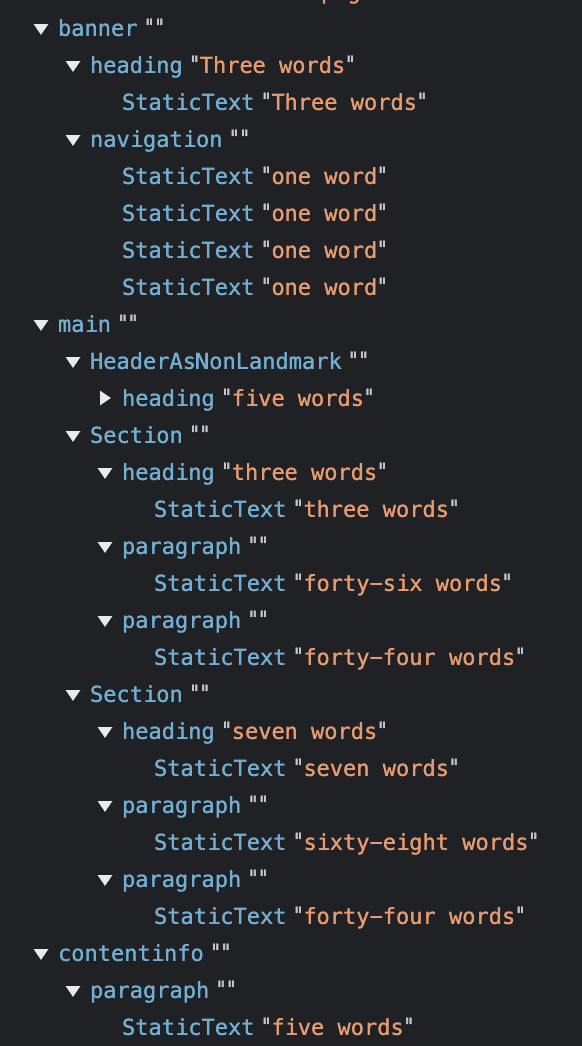

Semantic markup isn't just for making markup easier for developers to read; it's mostly important in helping automated tools decipher markup. Developer tools demonstrate how semantic elements provide machine-readable structure as well.

Accessibility object model (AOM)

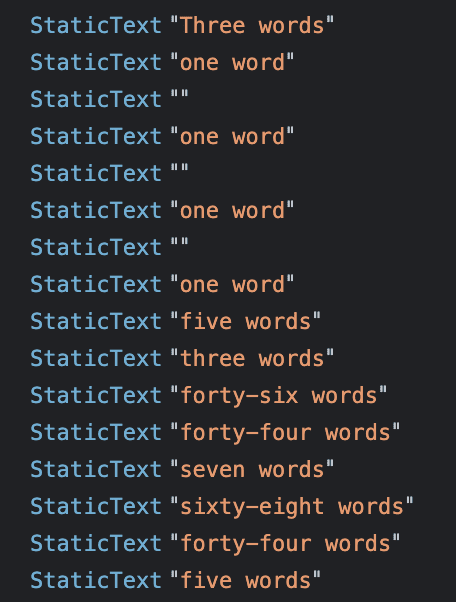

As the browser parses the content received, it builds the document object model (DOM) and the CSS object model (CSSOM). It then also builds an accessibility tree. Assistive devices, such as screen readers, use the AOM to parse and interpret content. The DOM is a tree of all the nodes in the document. The AOM is like a semantic version of the DOM.

Let's compare how both of these document structures are rendered in the Firefox accessibility panel:

In figure 2, there are four landmark roles in the second code block. It uses semantic landmarks conveniently named <header>, <main>, <footer>, and <nav> for "navigation."

Landmarks provide structure to web content and helps indicate important sections of content so that they're keyboard-navigable for screen reader users.

The <header> and <footer> are landmarks, with the roles of banner and contentinfo respectively, when they are not nested in other landmarks. Chrome's AOM shows this as follows:

Looking at Chrome developer tools, you'll note a significant difference between the accessibility object model when using semantic elements versus when you don't.

It's pretty clear that semantic element usage helps accessibility, and using non-semantic elements reduces accessibility. HTML is generally, by default, accessible. Our job as developers is to both protect the default accessible nature of HTML and maximize accessibility for our users. You can inspect the AOM in developer tools.

The role attribute

The role attribute describes the role an element has in the context of the document. The role attribute is a global attribute—meaning it is valid on all elements—defined by the ARIA specification rather than the WHATWG HTML specification, where almost everything else in this series is defined.

Semantic elements each have an implicit role, some depending on the context. As we saw in the Firefox accessibility dev tools screenshot, the top level <header>, <main>, <footer>, and <nav> were all landmarks, while the <header> nested in <main> was a section. The Chrome screenshot lists these elements' ARIA roles: <main> is main, <nav> is navigation, and <footer>, as it was the footer of the document, is contentinfo. When <header> is the header for the document, the default role is banner, which defines the section as the global site header. When a <header> or <footer> is nested within a sectioning element, it is not a landmark role. Both dev tools' screenshots show this.

Element role names are important in building the AOM. The semantics of an element, or 'role', are important to assistive technologies and, in some cases, search engines. Assistive technology users rely on semantics to navigate through and understand the meaning of content. The element's role enables a user to access the content they seek quickly and, possibly, more importantly, the role informs the screen reader user how to interact with an interactive element once it has focus.

Interactive elements, such as buttons, links, ranges, and checkboxes, all have implicit roles, all are automatically added to the keyboard tab sequence, and all have default expected user action support. The implicit role, or explicit role value, informs the user to expect element-specific default user interactions.

Using the role attribute, you can give any element a role, including a different role than the tag implies. For example, <button> has the implicit role of button. With role="button", you can turn any element semantically into a button: <p role="button">Click Me</p>.

While adding role="button" to an element informs screen readers that the element is a button, it doesn't change the appearance or functionality of the element. The button element provides so many features without you doing any work. The button element is automatically added to the document's tab ordering sequence, meaning it is by default keyboard focusable. The Enter and Space keys both activate the button. Buttons also have all the methods and properties provided to them by the HTMLButtonElement interface. If you don't use the semantic button for your button, you have to program all those features back in. It's so much easier to just go with <button>.

Go back to the screenshot of the AOM for the non-semantic code block. Here, non-semantic elements don't have implicit roles. We can make the non-semantic version semantic by assigning each element a role:

<div role="banner">

<span role="heading" aria-level="1">Three words</span>

<div role="navigation">

<a>one word</a>

<a>one word</a>

<a>one word</a>

<a>one word</a>

</div>

</div>

While the role attribute can be used to add semantics to any element, you should instead use elements with the implicit role you need.

Semantic elements

If you ask yourself, "Which element best represents the function of this section of markup?" you'll likely pick the best element for the job. The element you choose, and therefore the tags you use, should be appropriate for the content you are displaying, as tags have semantic meaning.

HTML should be used to structure content, not to define content's appearance. The appearance is the realm of CSS. While some elements are defined to appear a certain way, don't use an element based on how the user agent style sheet makes that element appear by default. Rather, select each element based on the element's semantic meaning and functionality. Coding HTML in a logical, semantic, and meaningful way helps CSS be applied as intended.

Choosing the right elements for the job as you code means you won't have to refactor or comment your HTML. If you think about using the right element for the job, you'll most often pick the right element for the job. When you understand the semantics of each element and are aware of why choosing the right element is important, you can make the right choice without much additional effort.

Next, use semantic elements to build your document structure.

Check your understanding

Test your knowledge of semantic HTML.

You should always add role="button" to a <button> element.

<button> element already has this role.